Messaging vs streaming: core architectural differences

"In this article, we explore core architectural differences between messaging and streaming concepts, define boundaries and discuss use cases"

There is a fair share of misunderstanding across even seasoned engineers when it comes to messaging vs streaming. I’ve seen developers - including myself in the past:) - struggle to clearly separate these two classes of systems and often mix concepts that are inherent to each.

If a company already runs on a streaming stack across the project, does it still need messaging? Usually, no.

If a company already relies on message queues, will it ever need a streaming platform? Often, yes.

Below I explore the core architectural differences of these systems to identify strengths, weaknesses, trade-offs and key use cases.

But first, let’s analyze the retrospective evolution of inter-service interaction in backend systems to better understand where we’ve been and where we are now.

Retrospective: evolution of async interaction#

Early era: RPC everywhere#

The first generation of distributed systems — roughly the late 1990s to mid-2000s — was dominated by Remote Procedure Call (RPC) thinking. Everything looked like a function call, but over a network. The industry mindset at the time assumed: networks are (mostly) reliable, latency is negligible compared to compute. As a result, systems behaved like one giant monolith distributed across machines. This stage introduced: a) synchronous semantics: every request blocks; b) tight coupling: caller and callee must be alive. Core problems were: if a downstream service slowed or died - callers froze or cascaded failures. E.g. a burst of 10k requests/s against a downstream that could handle ~3k/s caused blocking threads, queue overflow, retry storms — and the system collapsed.

Rise of Message queues#

By the early 2000s, the limits of synchronous RPC became painfully visible. The industry needed a mechanism that: absorbs load spikes, retries failures, decouples producers from consumers, does not require both sides to be online at the same time. Message queues became that mechanism — and they fundamentally changed how distributed systems were built. Asynchronous processing becomes natural: email sending, payment processing, invoicing, long-running tasks — finally handled off the main request path. Queues solved critical problems — but they also revealed new ones that later pushed the industry toward streaming systems: destructive consumption (no history, no replay), single-consumer semantic, no horizontal scalability, limited observability, like you see counts (e.g., “X messages in queue”) but not the full ordered sequence.

Rise of Distributed logs#

By the early 2010s, the limitations of traditional message queues became impossible to ignore. A new abstraction emerged to fill the gap: the distributed append-only log. Apache Kafka was the first system to popularize this log as a first-class architectural primitive, and this fundamentally changed how engineers thought about data, workflows, and system boundaries. The key innovations — non-destructive consumption, replayability, horizontal scalability through partitions, and multiple consumer groups — shifted the industry from task-oriented queues to fact-oriented event streams. This shift — from what to execute to what happened — was the key conceptual leap. Additionally, streaming engines like Apache Flink, Spark Streaming, and Kafka Streams added rich event-time semantics, windowing, and continuous computation, enabling new workloads: analytics, telemetry pipelines, fraud detection, ML feature processing, and event-sourced systems. Logs solved the intrinsic limitations of queues, and became the backbone of modern real-time architectures.

Now, it’s time to dive deeper into the internal architectures of messaging and streaming systems.

Messaging Queues#

As stated above, a message broker is a standalone, separately deployable application whose primary goal is to enable asynchronous task processing and service decoupling.

How it works conceptually?#

Producer. A producer (can be an application, device or a person) sends a message to a queue’s (topic, exchange or any other “front door”) over the network. The queue may operate in fire-and-forget mode or return a “publish confirmation” — either synchronously or asynchronously — indicating that the broker has accepted and persisted the message. Confirmation mode is recommended for applications where message loss is unacceptable.

Storage. At the broker side, messages are stored in format-agnostic form — raw bytes — the content is not inspected or modified by the broker. It is up to producers and consumers to agree on the serialization format. Most popular formats are JSON/AVRO/Protobuf, etc. However, in classic message queues, serialization format has almost no impact on throughput; for sustainable hundreds/few thousands RPS workloads and reasonably small messages (few Kb), JSON is a perfectly reasonable default due to its simplicity, readability, and universal tooling support. A message remains in the queue until it is acknowledged by a consumer (the broker receives a response from a consumer) or expires, if TTL (Time To Live is configured). Physically, messages are persisted on the broker’s local storage (SSD/NVMe), though exact placement depends on the broker type and durability settings (in-memory, disk-backed, replicated, etc.).

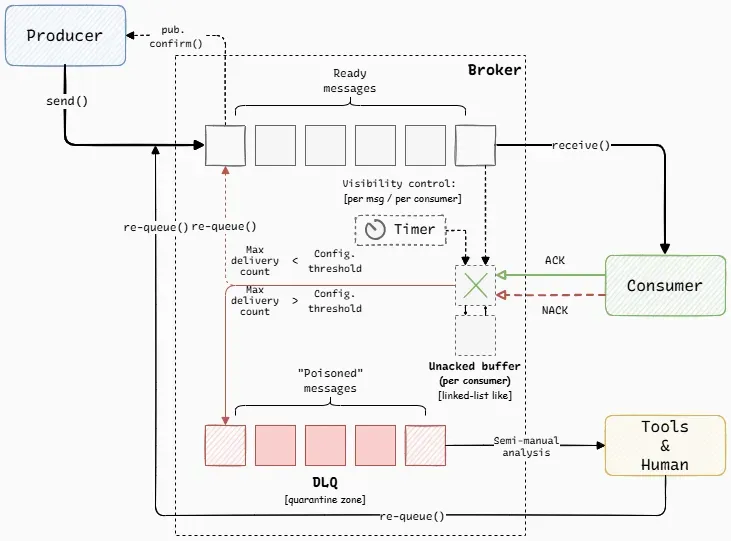

Consumers. Consumers may pull from the queue or receive pushed messages. This depends on broker type and configuration. In push-based mode, the broker typically tracks all connected consumers and distributes messages using a “round-robin” strategy. When a message is delivered to a consumer, it enters an unacked buffer (a linked-list-like structure per consumer, see Fig. 1) at broke’s side and remains there until acknowledged by a consumer. The “linked-list-like” description is an approximation(!) — different brokers may use alternative internal data structures with similar semantics. Once the consumer processes the message, it must send either an acknowledgment (ACK) or a negative acknowledgment (NACK) for that message back to the broker; upon receiving a positive ACK, the broker immediately removes the message from its internal storage and considers it fully delivered.

Re-delivery. Most brokers introduce some sort of “visibility timeout” (in terms of AWS SQS) - a small interval (measured in sec-s or min-s) during which a delivered message stays in unacked buffer and becomes temporarily invisible to all other consumers. An internal broker timer measures the time elapsed since the message was delivered to a consumer, see Fig.1. If the consumer crashes or fails to acknowledge in time, the broker automatically re-queues the message once the timeout expires. Re-queueing means the message is moved from the unacked buffer back to the main queue, making it eligible for delivery again. “Visibility timeout” is a broker-side protection against stalled consumers: it prevents messages from getting stuck unprocessed. Its behavior is broker-specific (per-message, per-consumer, or unsupported), and the timeout should be tuned to roughly match the expected processing time of a typical message. If it’s too short, messages may be redelivered prematurely, causing double-processing; if it’s too long, stalled consumers delay recovery and make callers wait longer.

Dead-lettering. Most brokers support dead-lettering, but it is not enabled by default — it must be configured at the broker or queue level. This is a special mechanism designed to handle poison messages — those that cannot be successfully processed even after multiple delivery attempts. You can configure the number of delivery attempts (say 3-5) after which the message is automatically forwarded to the DLQ (Dead Letter Queue), see Fig. 1. In most brokers, each message carries an internal delivery-attempt counter. Every failed, rejected, or timed-out delivery increments this counter. Once it reaches the configured limit, the broker’s routing logic automatically sends the message to the DLQ. Messages accumulated in a DLQ can later be inspected, corrected, and re-queued for processing.

Clustering. Brokers can be clustered and this is a typical production set-up. In a broker cluster, a queue is typically owned by one leader node and asynchronously replicated to follower nodes. But from the caller’s perspective the operation may appear synchronous because the system delays the acknowledgement until replicas confirm writes. This improves higher availability and fault tolerance, but does not make the queue itself horizontally scalable — all writes and reads still pass through a single leader. You cannot add a new broker node at runtime to increase the backlog capacity of an existing queue. For this reason, the storage size of each broker must be planned in advance to accommodate the expected backlog, unless you are using a cloud-native queue service, which can grow its storage capacity transparently (indefinitely in case of AWS SQS). Raft is gaining traction for building strongly consistent, leader-based queue replication, but many established message brokers continue to depend on custom, vendor-defined clustering mechanisms.

Conceptual model shared by most message brokers. Broker-specific storage / clustering details are intentionally omitted.

Streaming Platforms#

A streaming platform is also a standalone system, but it is designed for very high-throughput event ingestion — often hundreds of thousands to millions of events per second — while ensuring durability and supporting multiple independent consumers reading the same data. While streaming platforms are also asynchronous systems, asynchronicity is not their defining characteristic. So, let’s have a deeper look at how they work.

How it works conceptually?#

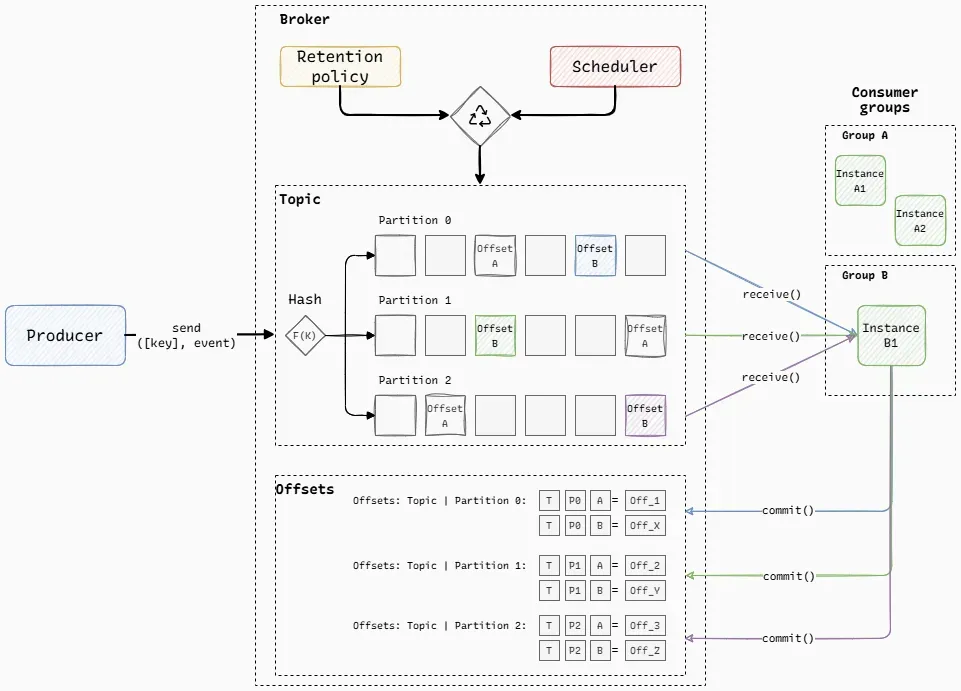

Producer. A producer (again being an application, device or even a human-triggered action) writes events to a topic and each event may include a key that determines ordering and routing. The streaming platform applies a hash function to this key to select a partition, which is simply an append-only, immutable log file, see Fig. 2. All events with the same key land in the same partition, preserving strict per-key ordering. Producers operate fully asynchronously: they append to a remote log without waiting for consumers or coordinating with them.

Streaming platforms also acknowledge writes to the producer — effectively the same idea as “publisher confirms”, just under different terminology. In self-managed systems (e.g., Kafka, Pulsar), the acknowledgement level is a first-class architectural decision because it defines how many nodes must persist an event before writing is considered successful (e.g. in Kafka ack = 0 | 1 | all). In fully managed cloud services (e.g., AWS Kinesis), this durability level is fixed by the provider and not user-tunable. This param directly defines how trustworthy the log is as a long-term source of truth and is typically chosen upfront as part of the system’s overall durability model.

Storage. Under the hood, each partition is an append-only, immutable log that grows sequentially on disk. Events are never mutated or removed on consumption — instead, they accumulate as a durable history that can be scanned, replayed, or compacted depending on the retention policy (see below). Because writes are sequential and disks are optimized for sequential I/O, partitions deliver extremely high ingestion throughput. Physically, events are stored as raw byte records with minimal metadata (offset, timestamp, and a small header). The broker does not interpret or validate the payload; just as in the case of message brokers, serialization is entirely the responsibility of producers and consumers. In practice, compact binary formats (Avro, Protobuf, etc.) often become essential at scale because they reduce both serialization cost and wire size, allowing the log to absorb significantly higher traffic. Overall, this durable log abstraction is what differentiates streaming systems from message queues: storage is not a transient buffer but an architectural primitive that preserves the full timeline of events.

Consumer (groups). Consumption is organized around consumer groups — coordinated set of consumers that together read from a topic as a single logical application. Depending on the platform, consumption may be pull-based (Kafka), push-based (Pulsar) or configured (AWS Kinesis). Multiple consumer groups may independently process the same messages. After processing records, consumers explicitly commit their new read position (offset) back to the broker that stores it durably, and then issue another fetch request to the partition for the next batch of events. Conceptually, this can be viewed as a persistent key-value table indexed by {topic, partition, consumer group} = offset, allowing consumers to resume exactly where they left off after failures or restarts ensuring at-least-once delivery semantics. The exact storage mechanism and coordination details are platform-dependent.

Because partitions are independent, consumer groups can scale horizontally: multiple instances within the same group divide the partitions among themselves, enabling parallel processing while preserving per-partition ordering. Rules that apply:

Rule #1

A partition can be read by at most one consumer instance in a group. This preserves ordering and prevents duplicate processing inside the group.

Rule #2

A single consumer instance can read from multiple partitions. When there are fewer consumer instances in a group than partitions, the workload is distributed by assigning several partitions to each instance.

These two rules are universal across all mainstream log-based streaming platforms as they fall out of the combination of the append-only log model, ordering and scaling requirements.

Fig. 2 illustrates how partitions are consumed by different consumer groups. Group B has a single instance (B1), so it receives all partitions of the topic. Group A has two instances (A1 and A2), so the partitions are split between them (for example, A1 reads from P0 while A2 reads from P1 and P2).

Retention (policy). Retention defines how long or how much data a log-based streaming platform keeps — independently of whether consumers have read it. This is very different from message brokers, where messages disappear once acknowledged. In streaming platforms, events remain in partitions for a defined retention period (hours, days, or indefinitely, e.g. in Kafka default value is 7 days), independent of consumer progress. The platform’s background sub-system periodically (every 5 mins by default for Kafka) evaluates log segments and removes or compacts old data according to the configured retention strategy — by time, by size, or a combination of both. Retention is what turns the log into a bounded, maintainable structure while still allowing consumers to replay historical data, rebuild state, or backfill analytics pipelines. Increasing the number of partitions increases parallelism and ingestion throughput, but it also increases the total stored volume subject to retention rules, making retention a key lever in balancing cost, durability, and performance.

Clustering. Clustering is typically more complex and more central than in classic message brokers. In practice, streaming platforms are almost never deployed as a single node and are architected for clustering by default — recovery, partitioning, replication, leader election, and consumer parallelism all rely on multiple nodes working together. A cluster presents itself as a single logical log system, while physically each node stores and serves a subset of partitions, allowing ingestion and consumption throughput to scale linearly as more nodes are added. Partitions are distributed across different machines, and each partition has an active leader along with one or more replicas placed on other nodes. The replication factor (RF) tells you how many copies of each partition exist in the cluster. Partition placement is determined by the cluster’s control plane — a specialized component responsible for metadata, coordination, and consistency. Producers always write to the leader, which then replicates new records to its replicas (usually asynchronously), ensuring that a node failure does not result in the loss of committed events. Consumers automatically rebalance when nodes join or leave the cluster, redistributing partition ownership to maintain parallelism and performance. This cross-node placement of leaders and replicas provides both horizontal performance scaling and the fault tolerance expected from a modern streaming platform.

Conceptual model common to log-based streaming systems. Cluster topology is intentionally omitted.

Conclusion#

Having explored both types of systems it becomes obvious that despite sharing some common features like async processing, decoupling producers and consumers, etc. these are completely different kinds of systems. And it’s time to answer the main question: how to choose the right system for a project? Unfortunately, there is no single recipe or universal algorithm for selecting a baseline system. What does work in practice is a small set of baseline strategies:

Start with messaging. Choose a message broker as your baseline if your domain is mostly tasks: emails sending, image processing, billing retries, webhook delivery, etc. You expect moderate amount of jobs, measured in hundreds, low thousands per sec. You are satisfied with destructive consumption: a message is taken from the queue and processed once, then after acknowledgement is removed forever.

Start with streaming. Choose a streaming platform as your baseline if your domain is mostly events / facts. You expect huge amount of events per sec (hundreds of thousands and even millions), that may increase in the future as system develops. You expect multiple independent consumers and evolving read-models. You need configurable retention and replay.

Hybrid. This setup is common in mature systems, even though is more expensive, and uses both streaming and messaging, with a clean boundary: streaming for event ingesting with potentially high throughput and messaging for operational tasks like delayed jobs with retries and native handling of poisoned messages. This avoids forcing one system to imitate the other.

Indeed, streaming systems can imitate messaging semantics by using a single consumer group, where each partition is consumed by only one consumer instance at a time, effectively approximating a distributed messaging queue. However, core messaging features such as retries, delayed redelivery, backoff, and dead-letter handling are typically not broker-native in streaming platforms and are instead implemented at the application level by consumers. This is most commonly achieved by forwarding failed records to dedicated error/retry topics, which are then consumed and processed according to application-defined rules.

Conversely, some modern message brokers provide streaming-like capabilities. For example, RabbitMQ offers Streams, including partitioned streams via Super Streams. However, this does not make RabbitMQ a full-fledged streaming platform in terms of ergonomics and operational model. RabbitMQ remains a general-purpose message broker and must support multiple messaging data structures and delivery semantics, which limits how far it can optimize around a single append-only log in the way Kafka does. Some community authors have also noted that RabbitMQ Streams and their client ecosystem are less mature than established streaming platforms, pointing to gaps in tooling, client libs behavior, and operational ergonomics observed in production scenarios.

Overall, message brokers are designed to solve a narrower class of problems, centered around task distribution and delivery semantics, and are not optimized for extreme ingestion rates or log-centric horizontal scaling. Streaming platforms, by contrast, are built to sustain high-throughput event ingestion and fan-out by treating the log itself as the primary scalability and durability primitive.

Ultimately, the choice between messaging and streaming should be driven by system scale, data retention needs, and consumption patterns — not by familiarity with a particular tool or ecosystem.